Does the changing economic landscape change the balance of power in Jones Act debate?

We’ve been covering the Jones Act recently on Project Puraka. A law that was designed to promote a robust domestic shipbuilding and operating industry by giving it a monopoly over shipments between U.S. ports. This was seen as vital to American national security based on experiences the country had during WWI. The law has come under fire from critics who claim that it has failed to achieve its national security goals and has added a hefty burden to the American economy in the process. These critics are demanding drastic reform, and total repeal in the extreme case.

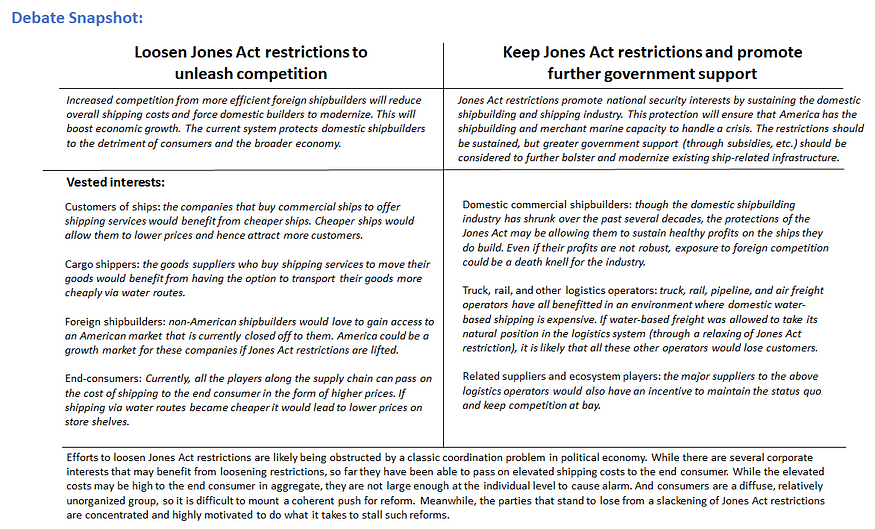

Today’s note is about how vested interests may be complicating the reform process along with some speculation about how America’s changing economic landscape could change the vested interest equation in favor of meaningful reform.

But first, a quick primer on the Jones Act for those who missed the previous pieces…

Jones Act primer

The Jones Act is a hundred year old policy that mandates that any shipments between two American ports must be carried in ships that are built in the U.S., crewed by Americans, owned by Americans, and registered in the U.S. It was created after the experiences of WWI led Congress to decide that America needed a strategy to ensure a robust Merchant Marine would always be ready in times of crisis.

The law ensured that American shipbuilders and Merchant Marine would have exclusive access to commercial intra-port shipping demand. This demand would be a source of funds allowing them to keep their operations and skills sharp. A robust commercial fleet and shipbuilding capacity would be a boon to the American economy and come in handy during wartime.

But that’s not how things have played out. Instead, the policy has insulated the domestic shipbuilding and logistics sector from foreign competition, inadvertently leading to inflated freight rates and pushing the brunt of America’s domestic cargo onto our roads and railways. The ability to construct large seafaring ships (the kind that would be most needed during wartime) has dwindled over the years. Approximately 60 shipyards have shuttered since the 1920s, leaving just 15 in operation today. Among those that remain, most of their demand comes from government contracts, not commercial contracts.

Meanwhile, the cost to the overall economy is high. The lack of domestic water-based transport (relative to what it could be) has an inflationary impact on the whole economy. Water-based transport is naturally less energy intensive than truck and rail. Shifting some freight onto water routes could reduce the overall cost of goods sold in the economy, not to mention place less burden on our road and rail infrastructure.

So clearly, there seems to be a need to do something. The status quo doesn’t seem like the best possible solution.

Vested interests

There is good reason to be cautious though. Reformers need to make sure that their reforms don’t leave us vulnerable to foreign shocks as happened during WWI.

Ideologically, the tug of war in the Jones Act debate is between the two powerful imperatives of National Security and Economic Prosperity. This principled debate is then complicated by myriad vested interests.

The current domestic water-based shipping industry has been operating under roughly the same policy paradigm (i.e. protectionist and government subsidized) for several decades now. The various stakeholders have organized themselves around the internal logic of this paradigm and some have likely gotten comfortable with the status quo. Any change to this logic could disrupt the current balance and usher in a new set of winners and losers. That is a possibility that the current crop of “winners” will want to postpone as long as possible.

Finding a practical solution is not easy; it will require clarity on priorities and certain vested interests will need to be mollified to enable successful negotiations.

The changing landscape of interests

Today, the global economic landscape is shifting in ways that may significantly change the vested interest calculation though. After decades of a pro-globalization posture, American institutions are aggressively investing in building up the country’s manufacturing base, especially for high technology products like semiconductors and electric vehicles.

Creating these products is a complex task, requiring hundreds of different steps spread across multiple facilities in a supply chain. Some estimate that a typical integrated circuit chip must cross more than 70 international boundaries before it is ready for market.

Products don’t get built in factories, they get built in manufacturing ecosystems, comprised of mines, factories, energy producers, and various other facilities. If the U.S. is serious about re-shoring manufacturing, it will have to build out these ecosystems, not just individual factories. And these ecosystems will need functional, efficient, and reliable logistics allowing the various players to move their inputs and outputs.

The cost of all that transportation gets factored into the final product cost. And manufacturers have every incentive in the world to try to drive down their costs. Doing things in America is just more expensive than in the many of the places where manufacturing happens today. Everything is more expensive here — labor, real estate, regulatory compliance, legal liability, etc.

Manufacturers will obviously look to automation to keep costs low. But if there is a law on the books in America that makes it prohibitively expensive to access maritime routes for transport, that, if removed could meaningfully drive down logistics costs, well, manufacturing executives are smart and they have a lot of financial clout.

Meanwhile, rebuilding America’s manufacturing base has become a bipartisan policy goal. In successive administrations, both Republicans and Democrats have pushed for creating greater economic resilience and industrial strength at home. Reversing the ill-effects of globalization on domestic manufacturing employment and capacity is an important issue for a large swathe of voters. Politicians across the board now have a political vested interest in making sure American manufacturing is Made Great Again, or Built Back Better, or whatever.

Not to mention that voters are also deeply frustrated with growing inflation and water-based transport is naturally (i.e. when unfettered by regulatory restrictions) cheaper than truck and rail.

The forces aligned on the side of meaningful reform, or even repeal, are growing stronger. We’ll have to wait and see if they gather their strength and aim it at changing the domestic trade paradigm on our waters.