Predicting De-globalization: Bruce Greenwald (Part I)

You take the Good with the Bad

This is the third installment in a series on analysts who were relatively early in predicting de-globalization.

What makes an economy ‘healthy?’ Is it the ability to generate a very high level of output? Or perhaps it is the ability to generate a high level of output at relatively low prices, so that everyone’s needs and desires can be reasonably fulfilled? Or is it the ability to generate a high level of output, at reasonable prices, without unnecessarily harming the broader environment in which everyone lives? Maybe an economy is healthy if it can just provide everyone with the basic needs of survival and everything beyond that is superfluous. Or maybe health is measured by how much freedom and ability people have to take risks and try new ideas. Or maybe it is a function of technological prowess.

Depending on how one defines ‘healthy,’ their ideas about how the economy should be organized, and their explanations for why things go wrong, will vary. Columbia professor Bruce Greenwald and his associates start from the insight that an economy is ‘healthy’ if it can produce a high degree of output while also providing sufficient employment for the people.

It is a good definition because it recognizes the circularity of the economic system. The economy exists to serve the people, and the people, in turn, serve the economy. “The people” contribute to producing the goods and services, earning them income, which “the people” use to consume those same goods and services. But what if circumstances evolve in such a way that one large chunk of the population is no longer needed to produce the goods and services they’ve been producing their whole lives?

Then the mechanism by which production is linked to consumption breaks down and the whole society experiences a painful economic slowdown. This is exactly what Greenwald believes happened during the Great Depression and again during the Great Recession of ’08. And his reasoning led him early on to the conclusion that the economy was heading towards a re-localization of economic activity.

Productivity shocks

To understand Greenwald’s hypothesis, we need to start with a sectoral model of the economy. Think of the entire productive apparatus of society as divided into three broad sectors — agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Each sector is unique, producing different kinds of output, requiring different kinds of organizational structures and different kinds of skillsets that don’t always easily transfer across sectors. All three are important to run a modern economy.

In a competitive marketplace, where businesses are constantly jostling for market share, nothing stands still for long. Every company is looking for a competitive advantage and this naturally drives everyone to seek out ways of increasing productivity. This is the logic that drives much of the technological progress in society.

When a new technology is found that can enhance the efficiency of producing widgets, every widget maker jumps to adopt the new technology. Widget output expands and prices fall. Suddenly, more people can afford more widgets. Profits rise as companies sell into an expanding market. Everyone is happy.

Seeing profits, companies invest more to build capacity and gain a greater share of the expanding market. Workers see widget-making as a safe and worthwhile profession, and train to build their skills. Capital in all forms — financial, human, etc. — flows into the space.

The process is self-reinforcing and accelerates…until it hits a point where there is no demand left for more widgets. At this point, the whole process begins to go in reverse, sending shockwaves of pain through the economy.

The capital invested into widget-making cannot be easily liquidated, so companies can’t just stop selling. Without a larger market to expand into, they have to jostle for space within the existing market causing prices to collapse. The only way to secure profits is by cutting expenses, including labor; incomes dry up across the industry. Widget-makers spend less because they are earning less, causing demand to decline across the economy.

In their 2012 paper titled Mobility constraints, productivity trends, and extended crises, Greenwald et al, define a term “economic importance” as a measure of a sector’s ability to generate revenue and potential employment. The above scenario demonstrates the “death” of the widget industry in economic importance. The ostensibly positive shock to the industry in the form of a new, productive technology eventually leads to a situation where the industry cannot sustain prices, employment, or profits.

If the widget industry were a small part of the overall economy, this would be an interesting episode that the rest of society might observe from a distance with sympathy and resignation. But what if an entire sector of the economy, which employs a sizeable chunk of the whole population, experiences such a productivity shock and “dies?”

That is a scenario that nobody escapes from unharmed.

The Great Depression

Here is an excerpt from Greenwald’s paper that describes the basic process by which productivity shocks produce economic death:

“Our analysis has at its root a model of persistent dislocation across sectors of a heterogeneous economy. In essence, persistent structural problems arise when a large but distinctive sector of a multi-sector economy experiences a major decline in economic importance — prices, revenues and potential employment. Most often this decline is associated with rapid but uneven productivity growth in the face of inelastic, relatively more slowly growing sectoral demand… if high productivity growth induces unexpected declines in earnings in this sector and if workers in the sector have most or all of their capital invested locally or there is not enough human capital for migrating toward a new sector, then the workers who must migrate may be sufficiently impoverished that they cannot cover the required fixed costs of migration and retraining. These fixed costs will be larger, of course, if the sector experiencing the shock is geographically isolated or entails skills that are different from the sectors to which it would like to migrate.” (Emphasis added)

Greenwald uses the Great Depression as a case study. Here is an excerpt from an old article I wrote that outlines the narrative:

“It is nighttime, 1893. The World’s Fair is being held in Chicago. The event marks the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to the New World. But this year’s fair is celebrating a different kind of exploration, not of geography, but of science…Thousands flood the festival’s alleyways, ogling at the marvelous new inventions on display, brought to life by the magic of electricity.

Meanwhile, the farmtowns of the Midwest have quietly been undergoing a Renaissance of their own. Armed with chemical fertilizers and the mechanical strength of inventions like the petrol powered tractor, farmers throughout the country usher in an unexpected era of prosperity. Large capital investments follow.

The next three decades see much of the same. New technologies like the automobile, radio, and washing machine improve productivity and lifestyles. Work becomes easier and home more comfortable, and America’s confidence in the inventiveness of its people is almost palpable.

Then…a divergence slowly takes shape. Productivity on the farms has grown rapidly. Prices have come down. Farmers, many of whom have taken on debt to buy the necessary land and machinery, face declining revenues. They turn to the government for help. In the cities, however, people only notice lower prices at the grocery store. Life is still good in the cities, in fact, it is roaring. Jobs in manufacturing are paying good wages. Standards of living are climbing and people spend more and more money on stuff. Confidence in American creativity is still very high.

The gods of finance smile on the city dwellers, revealing an intriguing new place for people to demonstrate their optimism. It is called the stock market. People funnel their disposable income into the equity of the country’s businesses. Some clever people become very rich by trading on margin. Others want to follow. Wall Street obliges.

In 1929, the party stops. There is too much debt and not enough demand. The farmers are stuck on the farms. They have to keep producing to pay off their obligations. They work even harder just to stay afloat. These farmers make up 1/3 of the country’s population. As their finances deteriorate, they stop buying things. Revenues collapse throughout the economy, then profits, then stock prices, then employment. In December of 1930, the Bank of the United States, the third largest bank in New York City, fails to close a merger. It faces a run and goes into bankruptcy (hmm…). Many more banks follow. The Great Depression is underway.”

The productivity boost that came with new machinery leads to overproduction. Eventually growth in production of agricultural goods surpasses the growth in demand for those goods. Prices, and hence revenues, are forced down. Not everyone can make the shift to find more lucrative work in the manufacturing sector which is concentrated around cities. The sheer size of the agricultural sector, employing nearly 1/3 of the population, means a drop in demand from that sector is felt throughout the economy. Eventually, even the booming manufacturing sector cannot escape such a decline in demand. Revenues decline across the economy. Business activity grinds to a halt.*

The reality of limits

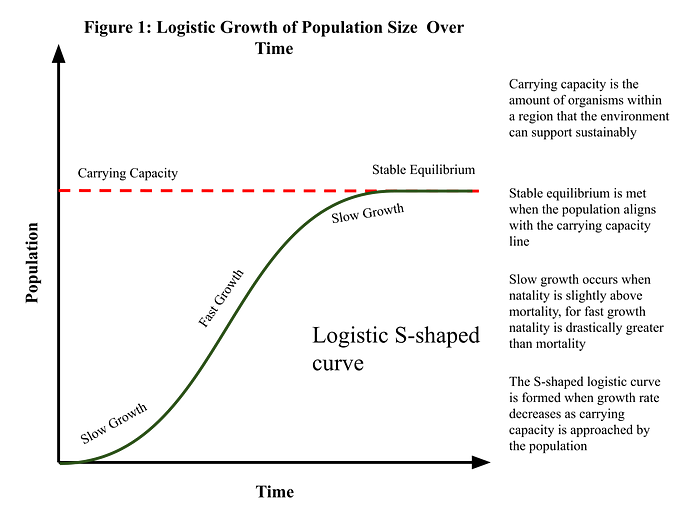

People who study physical systems are familiar with the concept of carrying capacity. A system can only support so much of a certain variable before it breaks the whole system down. A house can only hold so many residents before it becomes too chaotic to manage, a field can only hold so much cattle before there isn’t enough vegetation to feed them, etc. Carrying capacities are why we rarely see exponential curves sustain forever in nature. Something can grow exponentially for a while, but when it reaches the limits of what its environment can support, it’s growth will plateau.

The key relationship in Greenwald’s model, is between productivity growth and demand growth. If demand growth outpaces productivity growth, new technologies cause an increase in “economic importance.” Everyone associated with the sector benefits.

Demand growth outpacing productivity growth implies that the more efficient production is finding latent demand. As prices come down, more people can afford the output of the sector; the addressable market is expanding. Producers can offset lower unit prices with higher sales and still generate higher profits.

This is an example of competitive markets working well. Competition forces firms to relentlessly search for more efficient ways to produce their output. This allows more and more people to afford this output as time passes, ensuring that no desires go unfulfilled.

But at some point an invisible threshold is crossed; productivity growth begins to exceed demand growth. Initially, the change may be so slight that most sector participants may not even notice. There is still plenty of demand to support current levels of production. But according to Greenwald’s model, this marks the beginning of the end; the sector has entered an entirely new regime and is on its way towards death.

It is demand that justifies and feeds the whole process of production. An economy can only consume so much of a certain type of output before it simply doesn’t want any more. According to Greenwald, this overproduction is what killed the agricultural sector in the early 1900s and sparked the Great Depression.

In Part 2…

In Part 2, we will see how this same model can be applied to make sense of the Great Recession that began in the late 2000s. The nuances of the situation are different. This time, the “dying” industry is not agriculture, but global manufacturing. And according to Greenwald, a consequence of this “death of manufacturing” will be a return of “economic importance” to industries that are local by nature.

*To test this model out, it’s important to test the sequence of events. Did revenues drop precipitously in agriculture well before the slowdown hit the rest of the economy? Though I don’t have data handy to show this, that does seem to be the case. It’s well documented that the American farmer was already struggling and lobbying the government for support even before the start of the “Roaring 20s,” which preceded the start of the Depression.

Another question to consider is, if the farmers were struggling to earn an income on their farms, why didn’t they move to the growing manufacturing sector in order to secure higher incomes. Many farmers did, in fact, move to the cities; Greenwald et al provide some data on this migration.

“In the US, farm population, which declined from 29.9 to 24.8 percent of the overall population from 1920 to 1929, fell by just 1.4 percentage points to 23.4 by 1940.24 The fall in agricultural prices can be thought of as purely redistributive: farmers lose, those in the urban sector gain.25 The resulting decline in rural demand for industrial output would have outweighed any increase in urban demand as long as the marginal propensity to increase consumption by urban households was lower than the marginal propensity to reduce consumption by rural households. Several factors made such an outcome likely.”

There are obviously non-economic reasons why someone would be reluctant to leave their land and their way of life even if financial pressures are strong. The tragic irony of the situation is that, as the value of their assets collapsed in the face of overproduction, many farmers resorted to trying to produce even more to bring their income and asset values back to par, accelerating the problem of overproduction.

In the 20s, the farmers that could afford to move and had the desire, did move. However, a significant amount remained on the farm. After the Great Depression began in earnest in 1929, movement collapsed. This is likely due, in part, to the fact that manufacturing jobs also dried up once the Depression hit.

“Our analysis argues that market processes themselves may not lead to “good” outcomes. Information is imperfect and costly to obtain. The result is that capital and labor markets work markedly different from the way that they are assumed to work in neoclassical models. Credit and labor markets may not clear. Even though rural workers could increase their income if they could costlessly move to the urban sector, the move is not costless, and they may not be able to obtain the requisite capital. Note that there are three distinct “market failures” (we hesitate to call them that, because it is not a failure that

information is costly or that labor mobility is costly, any more than it is a failure that to obtain outputs, one must put in inputs): (a) mobility is costly; (b) individuals may not be able to obtain funds; and c) there are (real) wage rigidities in the urban sector.”

Hope you enjoyed this article. If you have any comments or critiques, please share!